Last year, I was at a kid’s birthday party at a warehouse full of bouncy houses. The parents stood around with their attention half on conversation and half trying to keep track of their young children as they darted in and out of the various inflatables. As we tried to monitor our kids, I struck up a conversation with another dad.

I asked him what his kids liked to do and he started ticking off a number of hobbies ranging from art to Legos to different sports.

Stunned, I responded, “Wow, all my kids like to do is watch screens.”

He laughed and said, “Oh, I thought you meant other than screens.”

This is the life of a parent with young kids and, I imagine, with older ones as well. Screens dominate our kids’ attention to the point where a day is often–in their minds–scheduled around screen time. On the weekends, we will usually declare the day’s schedule at some point in the morning to our kids, whom I will affectionately henceforth call the “Hobbitses,” and follow-up questions often center around “when will we get screens?” Screens are, to be sure, their Precious.

Screens, to our Hobbitses, refers to a combination of tablet (YouTube and games) + computer (Roblox and more games) + Nintendo Switch. It doesn’t even necessarily mean the TV anymore, and the Hobbitses haven’t sniffed social media beyond YouTube.

We try to follow the recommendation listed on the posters hanging at the pediatrician’s office urging no more than two hours of screens per day. That’s easier during the week when school and extracurriculars fill up much of the time. On weekends, it’s a different story. They will blow through two hours before breakfast. Although, we have implemented a hard cut off of 30 minutes for YouTube because, frankly, YouTube is filled with hot trash.

We aren’t the only ones in this boat. Many a-family know the allure of the Precious and the strife that comes when it is either denied or cut off. Those who maintain “reasonable” levels of screen time usually adopt a rigid–or sometimes Draconian–policy limiting access. Problem solved, right?

As the saying goes, “if it was that easy, everyone would be doing it.” Like many problems that persist today, this issue is more complicated than it appears at first glance. Precious, like onions and ogres, have layers, and it affects more than just the kids.

What’s the problem?

Like any business, the companies who build the products that are delivered on the Precious want us to use them as much as possible. This is how pretty much every for-profit company operates. In this case, if the companies aren’t directly charging us for something, like the cost of an app, goods on a shopping site, or in-game/in-app purchases, they are harvesting and selling the data we give them, wittingly or unwittingly. As former Google employee and tech ethicist, Tristan Harris, has noted: if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.

It might be stretching the Lord of the Rings metaphor to collectively call these companies Sauron, but you know what, whatever. We’re calling them Sauron.

So, if Sauron acts like any other business, by trying to make the Precious as attractive as possible to turn a buck, what’s the problem? That’s how capitalism works; I thought this was America.

Well, the problem is that Sauron forged too powerful a ring. One ring to rule them all has led us to compulsive, perhaps even addictive, behavior. Sauron understands enough about what makes the human mind tick and has exploited it with ruthless efficiency.

One tactic utilizes randomized rewards, or “intermittent reinforcement.” Think of slot machines: Every time you pull the lever, you have a chance to make money; but really, you rarely do. It happens just often enough that you’re willing to put another quarter in the machine for another chance to hit it big. It’s that chance that keeps us coming back. (Come to think of it, this is how it feels playing golf–one good shot keeps you motivated even when the rest of your shots go into the woods.)

Other tactics capitalize on our innate desire to connect with others and the social validation feedback loop: That subtle, warm feeling we get through likes, shares, and follows that pushes us to seek others’ attention. Another tactic is the algorithms delivering us tailored content to keep us engaged curated by the data pulled from our online activity. For a deeper dive on how Sauron manipulates us through social media specifically, check out the Social Dilemma.

To be sure, when I describe Precious, I’m referring to a broader category of screens and technology, but social media platforms come to mind as the biggest culprits hacking our minds. While it may provide the most egregious examples, they aren’t the only ones using these tactics.

Ok, so what’s really the problem?

We all know how this makes us feel. We have all sat there scrolling our phones or playing games telling ourselves “I’ll just do it for another minute” and then ten, twenty, thirty minutes (or more) float by. Yes, anything that we find interesting can have that effect, but we know this is different. How many of us have had to delete apps from our phone because it seems like the only way to avoid the pull? And if it’s like that for adults, kids don’t stand a chance.

Part of the reason this kind of existence persists is because we’re still in the infancy of the Precious, specifically smartphones and social media, and haven’t fully quantified its ramifications. There is some science on how it affects us, but we’re really just beginning to understand.

More importantly, Sauron knows its products harm people. In 2021, Frances Haugen came forward as a whistleblower against Facebook revealing, among other things, that it is well aware of how toxic Instagram is for teenage girls.

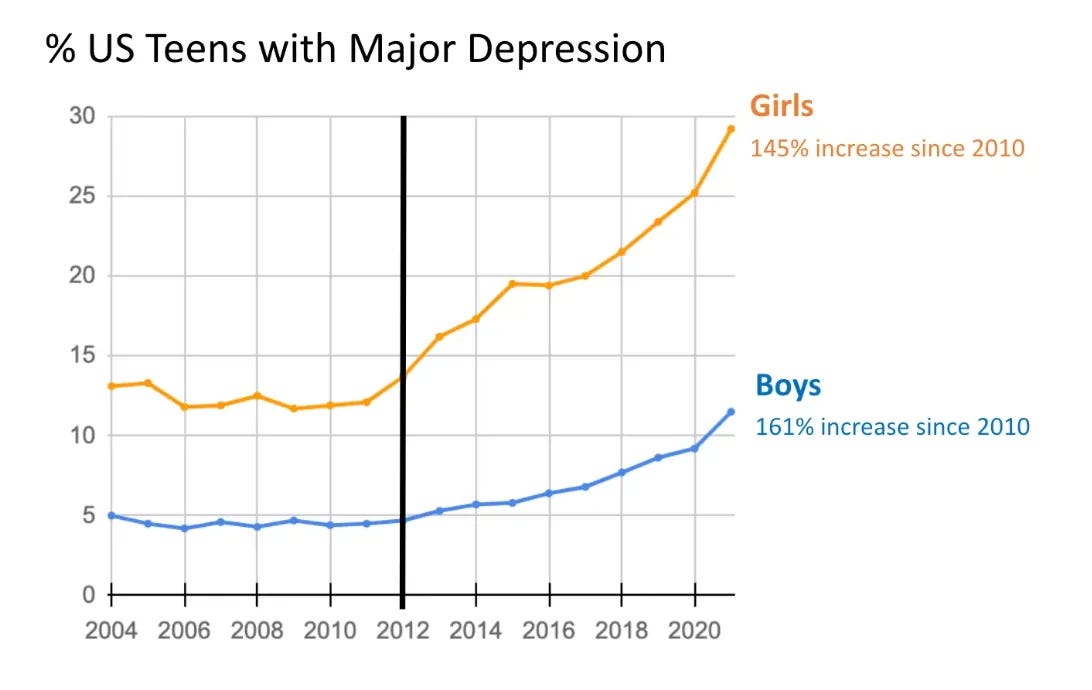

Percent of teens with Major Depression in the last year. National Survey on Drug Use and Health data, see section 1.1.2 of the Adolescent mood disorders collaborative review doc.

When you’re looking at a chart like this, keep in mind that the first iPhone was released in mid-2007 and Facebook took over Instagram in 2012. Similar trends have been recorded for U.S. teen anxiety and self-harm, and the U.S. is not alone. Trends like this are still only considered correlated to social media and smartphone use, but I’m not aware of another theory that can explain them. The warning signs are flashing even if we don’t have all the data establishing airtight causation.

The People vs. Sauron

This article was inspired by the lawsuit filed by over 30 states against Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, alleging that its business model targets and exploits minors for profit and falsely represents that its products are safe for young users. How this suit proceeds will be illuminating on how our current U.S. laws can combat Sauron’s overreach. For it is a great example of everything we’re concerned about: Social media companies (the most proficient at polishing Precious’s shine) exploiting kids (the most vulnerable) for profit.

The states should be able to learn even more about Meta’s approach and what it knows about the ill effects of its products during discovery, the information gathering part of the lawsuit where Meta will be obligated to share some of what it knows. Meta will do everything it can to prevent this information from reaching the public, but there’s little doubt that some will leak.

It’s tempting to draw parallels between this case and that against Big Tobacco, namely that in both cases you have large companies who intentionally made their products addictive while knowingly concealing the harms. However, there are distinctions. By the time Big Tobacco was seriously challenged, it was established that one common side effect of tobacco use was death along with a litany of other negative health outcomes. And the benefits offered by tobacco? They pale in comparison to the cons so much so that you almost never even hear them mentioned.

However, we don’t have the luxury of decades of data on the impacts of social media, and it does offer legitimate benefits. We’re able to connect with friends, loved ones, and strangers in fun and meaningful ways. Information can be shared easily, it helps small businesses grow, and the platforms have democratized the world for content creators. So, it’s hard to envisage a total take down of Meta from this case.

If a judge or jury does rule against Meta for their behavior, what does it mean for other industries who use similar methods to keep us hooked on things like processed food? Could this be the first domino to fall so that companies will be discouraged from manipulating consumers? It’s overly optimistic to think it will have that much of an impact, but it could lead to some progress.

The bottom line is that the extent that Meta, social media, and other companies have gone to compel us to use their products is not OK. We should not accept that this is another “willpower” thing and we can just stop using all these products and go off the grid. Further, the notion that they do not target kids and have implemented effective safeguards is laughable to the point of insulting.

Surely we can enjoy the benefits without Sauron digging its hooks in our brains. Hopefully, we will see a day soon when its wings are clipped. This case and other legislation passed around the U.S. and the world in recent years has started the ball rolling in that direction. But let me know when it’s safe enough to reinstall some of the apps I’ve deleted over the years.